In most industrial plants, something happens that baffles maintenance teams: a bellows that previously functioned perfectly begins to rub, open, or deform, without anyone having made any obvious changes to the machine. The operator hasn’t touched any critical parameters, the integrator hasn’t intervened recently, and production continues as normal. Even so, the guard fails.

These situations aren’t due to material errors or manufacturing defects. In the vast majority of cases, the cause is simpler: the machine has subtly changed, even if no one has noticed, and the bellows—which depends entirely on the movement—no longer operates within the conditions for which it was designed.

This article explains why this happens, what signs indicate it, and how to prevent it with properly sized industrial machinery guards.

.

1. A bellows is not a static part: it depends on the actual movement of the machine.

A bellows is designed to move with a shaft, guide, or mechanical assembly. Its function is not just to cover, but to guarantee reliable protection for industrial machinery, preventing the entry of contaminants, the exposure of components, or premature wear of critical areas.

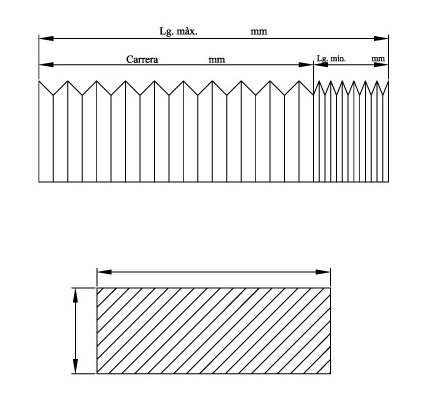

Each bellows has:

- A maximum stroke.

- A minimum stroke.

- A geometry designed for the available space.

- Folds designed to operate without tension.

- A specific compression/extension range.

If any of these parameters no longer match the actual movement, the bellows will begin to suffer.

Therefore, even minimal changes can directly affect its performance.

2. Common micro-adjustments that alter dynamics without anyone noticing

In production, many adjustments are considered “insignificant.” And they are… except for the bellows.

Here are some very real and frequent situations in any plant:

– Adjusting stops without recalculating the total stroke

A displacement of 3–5 mm can cause a fold to compress more than intended.

– Replacing a tool with slightly different dimensions

The new tool may require different positioning, even if it isn’t perceived as a significant change.

– Relocated or calibrated sensors

Millimetric changes at the origin or end of the stroke create new demands on the bellows.

– Reassemblies after maintenance

A guide mounted with a slight deviation alters the bellows’ trajectory when opening or closing.

– Changes in acceleration or speed

Improving cycle time can generate inertias that didn’t exist in the original design of the guard.

None of these changes seem problematic. But for a bellows, which depends directly on movement, they are.

3. What symptoms indicate that the bellows is no longer working within its correct range?

If a bellows is out of tolerance, it always leaves clues.

These are the clearest:

1. Shining appearance on a fold

Shine indicates friction.

It is an early sign that the material is being stressed.

2. Folds that don’t fold as well as before

A change in the operating geometry usually shows irregular compression.

3. New sounds: slight rubbing or soft knocks

Don’t wait for loud noise: minimal rubbing is enough to shorten the bellows’ lifespan.

4. Material under tension at one end of the travel

It is common to see how a fold “pulls” more on one side than the other.

5. Micro-deformations after rapid cycles

Accelerations make hidden stresses visible.

Detecting these signs in time prevents breakage and more serious problems.

4. Why a Bellows Stops Protecting Even When It Looks “New”

When the dynamics change, the bellows may still look good on the outside, but it stops fulfilling its function.

The usual consequences are:

- Dust or shavings entering through micro-openings.

- Tension in the folds, causing premature deterioration.

- Contact with surfaces that wear down the material.

- Excessive compression that reduces its lifespan.

- Partial blockages during long travels.

This explains why many guards for industrial machinery fail “suddenly”: the problem had been developing for some time, but it hadn’t yet become visible.

5. How to avoid these types of failures without modifying the machine

The solution isn’t simply replacing the bellows with an identical one.

If the movement has changed, the bellows must change as well.

The correct process for ensuring reliable protection of industrial machinery includes:

1. Reviewing the machine’s actual stroke

Not the one shown on the drawings, but the one it has today.

2. Analyzing the available space

Even millimeter variations matter.

3. Identifying where excessive tension or compression occurs

Observe the entire cycle, not just a single moment.

4. Redesigning the bellows geometry

Adjusting fold height, extension, and compression.

5. Adapting fixings and overlaps

To ensure a watertight seal and stability.

When a bellows is sized for the actual movement, it provides efficient and lasting protection.

Conclusion

A bellows doesn’t fail for no reason.

It fails when the machine no longer moves as the bellows is designed to.

Therefore, in industrial environments where production is constantly evolving, reviewing and recalculating the protections for industrial machinery is essential to avoid silent breakdowns and extend the useful life of the equipment.